April 10, 2006

Bonafide British Person C.J. Quinn covers the strange intersections between British television and American television in...

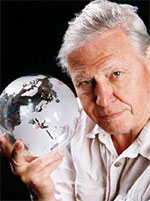

London CallingDavid Attenborough Shows You The World

|

Now about to enter his eighties, the man is an absolute legend. For decades now, he has brought the natural world into Britain's living rooms, surveying every aspect of life on our planet from monsters of the deep to mini-beasts in the shrubbery. The famous trilogy of series, Life on Earth (1979), The Living Planet (1984) and The Trials of Life (1990) were grand sweeps examining the world's rich variety of species, habitats and stages of life — later he turned to more specific topics such as Antartica, insects, plants, birds, mammals, and marine life.

David Attenborough is probably one of the BBC's most valuable brands. You know right away what you'll get when you hear those hushed, enthusiastic voice-over tones — breathtaking photography; fascinating natural science made comprehensible for family viewing, without stooping to patronise; a heartfelt, although not strident, plea for humans to be better caretakers of our world, and the comforting presence of one of TV's favourite grandpas to guide you through the world of natural wonders (in a poll this year, Attenborough topped the list of the 100 'most-trusted' Brits). When he was younger and somewhat more limber, Attenborough himself would often clamber into the frame in his programmes, unable to keep the grin off his face while whispering into the lens six feet from a family of mountain gorillas, for example. These days, he sticks to narrating from off-screen, in a voice as British and as comforting as a hot-water bottle on a cold night.

| A new Attenborough series is a landmark event, and the best kind of water-cooler TV, because you actually feel cleverer for having watched it. |

The series has taken ten years to put together, and it shows. Not a second of footage is dull or superfluous, and new filming techniques have allowed the BBC's Natural History Unit team to bring unbelievably vivid spectacles to the screens. Planet Earth makes stunning use of satellite and aerial filming to show us giant dust storms sweeping the Sahara, millions of caribou crossing the tundra in the world's largest land-based migration, or the Siberian taiga and African Okavango delta bursting into green life as spring arrives. The camera lens seems to swoop, soar, float and descend like some great bird of prey, and can take us from high above the planet to the specific, singular drama of a wolf chasing a lone caribou across the tundra, or an elephant and her baby lost in the swirling dusts of the Kalahari.

|

Heart-stopping, breath-taking, stirring — this is the first series I can remember in a long time that has really lived up to those descriptions. I found myself on the verge of tears at the end of the first episode, in the way that just occasionally a really great piece of music or theatre can stir up inexplicable emotion. There are moments in Planet Earth when you find yourself literally holding your breath in disbelief, heart racing, such as the sequence showing Great Whites attacking sea lions off the coast of South Africa. Film of a striking shark was slowed to 1/40th of a second to show how the giant muscular bulk of the fish leaps and twists as the jaws close around the prey, lifting its entire body several feet clear of the water before it crashes back down. Slowed down this much, the footage looked like something out of The Matrix, a spray of water droplets barely moving around the fish's soaring and thrashing body.

| I find myself in complete agreement — this is what the BBC does, and what it should keep doing for generations, public-service broadcasting at its best. |

Email the author.

Return to Season 2, Episode 14.

All written content © 2005 - 2006 by the authors. For more information, contact homer@smrt-tv.com