April 18th, 2005

In the world of television, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: the writers and producers of hour-long crime dramas, and the viewers, who watch said dramas. These are their stories.

Be Careful Out ThereWho Says You Can't Kick Ass in High Heels:

The Pantsuit and Gender Equity

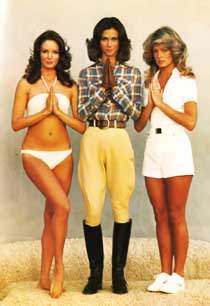

Once upon a time, woman had integral roles on cop shows.

The pre-pantsuit days. |

Then came the '80's and women in uniform. But no beat cop ever wore her badge with as much cleavage as TJ Hooker's Officer Stacey. And while Hunter touted DeeDee McCall as a tough-as-nails cop, our first glimpse of McCall, a dressed-up and pimped-out cop playing a call girl, was the epitome of an '80's cop show clich³. It was a case of all tell, and very little show. Not that it mattered, because DeeDee McCall was 100 percent sidekick. The show wasn't called Hunter and McCall, but it might as well have been called Vehicle for Former Football Star Fred Dryer.

And I don't even want to talk about those girl cops on Miami Vice„ one slept with Crockett in the first episode and spent much of the series mooning after him, while the other ended up sleeping with Tubbs. True to its name, Miami Vice offered viewers episode after episode of the female officers dressed up and pimped out, riding that trope all the way down Miami's seedy beaches, Elvis yapping at their heels with his pointy crocodile teeth.

That's why when Lucy Bates hit the TV in our house it was a revelation. In my house, snark about TV was snark before snark was snark. My dad personally coined the term Battlestar Godawfulica, and I watched Hunter in secret at my grandparents, who were adoring and happy to thwart my father. They also let me watch Matt Houston, so perhaps a little filtering would have been a good thing. But back to Lucy Bates.

Lucy was a real female cop. She had bad hair and an ill-fitting uniform, blending seamlessly with the lovely, gritty ensemble drama that was Hill Street Blues. Technically, Hill Street predated Miami Vice and Hunter but the lasting effect of Hill Street's female portrayals is more apparent in later TV than in its contemporaries. Officer/Sergeant Lucy Bates was committed to her job. She fumbled occasionally, had her fair of issues and was in love with her partner, but it was an embarrassing sort of affection, an unrequited and wordless thing that didn't interfere in the way she did her job. Lucy was the uniform, the girl in blue, not a sex symbol or a joke, but a female cop with a fully formed personality.

As Homicide: Life on the Streets was the natural heir to Hill Street, so Lucy Bates gave way to Detective Kay Howard, with her biggish hair and bad suits. Howard might have been the only whiff of estrogen in that shabbily furnished police station in Baltimore but her character was never the token girl on the screen. Howard had her fair share of issues, and maybe she didn't have Pembleton's flair or Bayliss's compassion but she was competent cop in her own right, with the perfect solve record to show for it.

The legion of female cops currently coasting our airwaves owes a debt to their predecessors, both in terms of roles and wardrobes. It's hard to imagine Olivia Benson in a miniskirt, although less difficult to picture Catherine Willows showing some skin. Their presence can be traced and analyzed through clothing as easily as through the evolution of sexual stereotypes. While women lost the short skirts, they may have also lost their unique femininity, descending into a new brand of stereotype.

The last Tahari suit skirt I remember seeing on a female member of the TV Law Enforcement community was on one Dana Scully, late of The X-Files. And, I remember distinctly, she wore it well. Since then, we've been living the era of the pantsuit, clothing far more suited to police work than high heels and pantyhose, but nonetheless pantsuit has come to equal girl cop in the same way that a single white glove equals Michael Jackson.

Law and Order: Criminal Intent's Detective Alexandra Eames, Cold Case's Lilly Rush, Numb3rs' Terry Lake and all of the ladies of the various CSI's wear their pantsuits proudly. While Catherine Willows may have invested in a super secret brand of Scotchguard, for the most part, the clothing seems to fit the job. It's professional, it's moveable and it takes women out of the realm of sex object and puts them firmly into the world of squad member. However, unlike Kay Howard's not so attractive neutrals and Scully's early ill-fitting, pre-Los Angeles and a non-Canadian wardrobe mistress days, the current crop of pantsuits is designed to turn all the female cops into clones of each other. I may know the names of the actresses in the various procedurals, but I can't seem to remember the names of the characters they play: they're that interchangeable. They've got the same fitted button down shirts or stretch jersey long sleeved T's, the same tailored pants and jackets„the same bloody haircuts for that matter„to the extent that it seems to me that we've only traded one uniform-based clich³ for another. Has the pantsuit given us gender equity, or is it merely a more professional way to relegate the female detectives to second string?

Everybody in pantsuits! |

The hard drinking, relationship phobic, competent and passionate detective is a new kind of female cop, but this is hardly a case of individuating the women in these roles. Yeah, Scully wore ugly pantsuits and high heels, but she was fully realized in her personality. Lucy Bates wore her blue uniform, wore her job on her body, but she wore it proudly. The uniform didn't hide her identity, it set her apart in the largely male world, not exactly tailored for her body, just as the job and the environment was not exactly tailored to her gender. Kay Howard wore a skirt suit to court, and it was just as ugly as the beige pantsuits„ Kay inhabited her existence fully, heard ghosts and had doubts and was good at her job and boinked the DA. Lilly Rush may be the only female detective in her Philadelphia homicide division, but she fits in so well as a driven women that there's very little in the character that distinguishes hers as a girl. Her clothing shows that while she may be the lone female, she's part of the process, part of the establishment. It's a way to dismiss the complications and conflicts she deals with as a woman in a predominantly man's world. If she looks enough like the men, takes away character, sexuality, individualism, we can read the conflict into our history of TV and never have to deal with it outright. In the same way, it's hard to see pretty and petite Sabrina Lloyd, barely serving a purpose on Numb3rs but with her pantsuit is in full effect. It seems a shame that the girl who fully inhabited Sports Night's Natalie Hurley and her short skirts and leggings is relegated to supporting Rob Morrow as a sexless sidekick, competent or not.

The pantsuit is not only taking away from female individuation, it is robbing the women of their sexuality. They can't exactly be girls when they're limited to one particular style of dress that carries with it the same range of messages that the '80's power suits and big shoulder pads did. The suits, and the characters, scream, "Yeah, I'm a girl, but not too much of a girl. I'm transcending old gender roles while creating a whole new set of them." I'm all for gender equity, all for losing the clich³s and I'm certainly happy to see women represented as partners and bosses and coroners, but I'm not sure that we've achieved real equity, not sure that we aren't robbing these female characters of the chance to inhabit the roles as women with their own unique strengths, weaknesses and fashion sense.

Email the author.

All written content © 2005 by the authors. For more information, contact homer@smrt-tv.com